Patterns for building realtime features

Realtime features make apps feel modern, collaborative, and up-to-date. The features predominantly require sharing changes triggered by one user to other users, as the changes are happening.

This typically means your server needs to send data to some set of clients, where those clients don’t know they are missing the data.

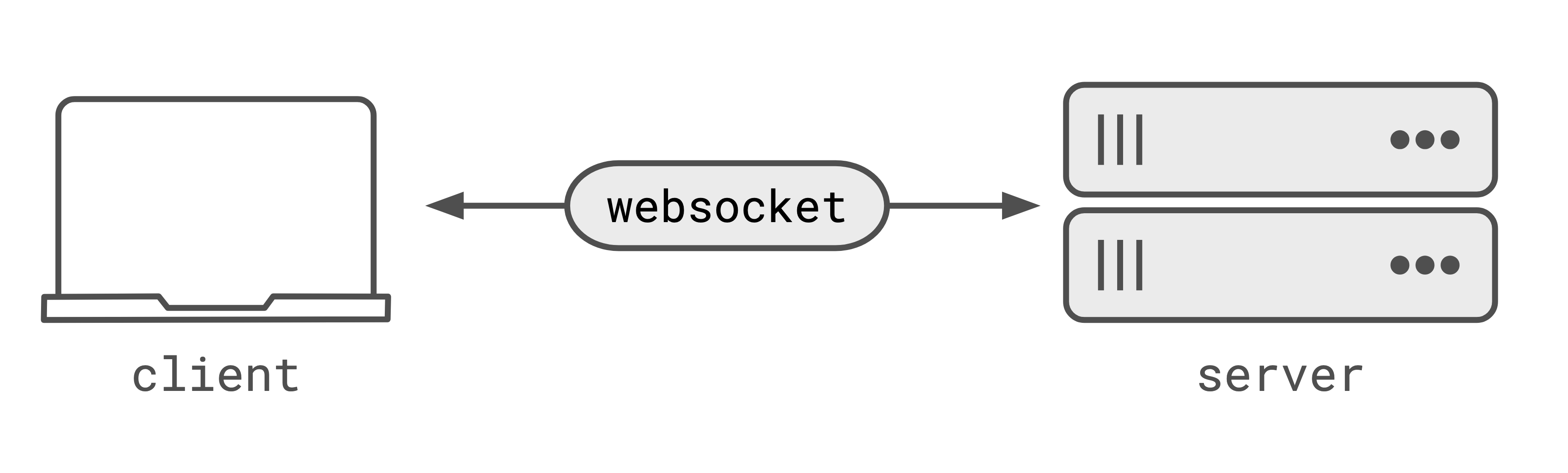

These patterns rely on a connection between the client and the server, where the server can notify the client of some data. This connection could be websockets, sse, event-streams, or polling (long or short). The connection just needs to allow the server to send data to the client without the client knowing that there is new data.

Patterns

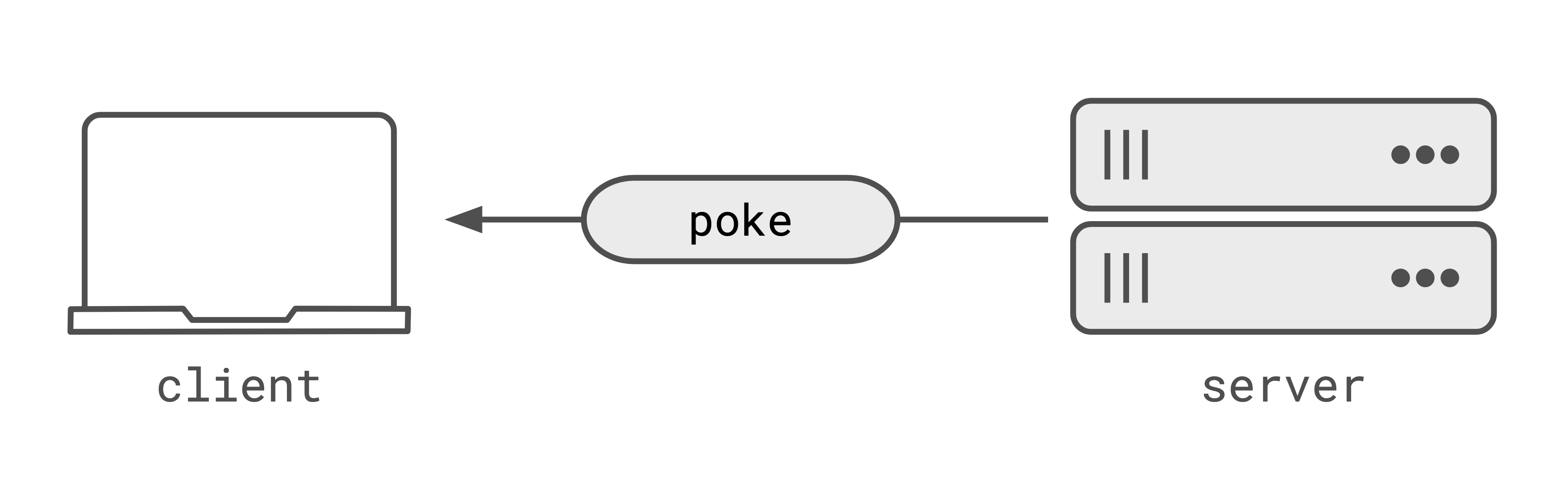

Poke/Pull

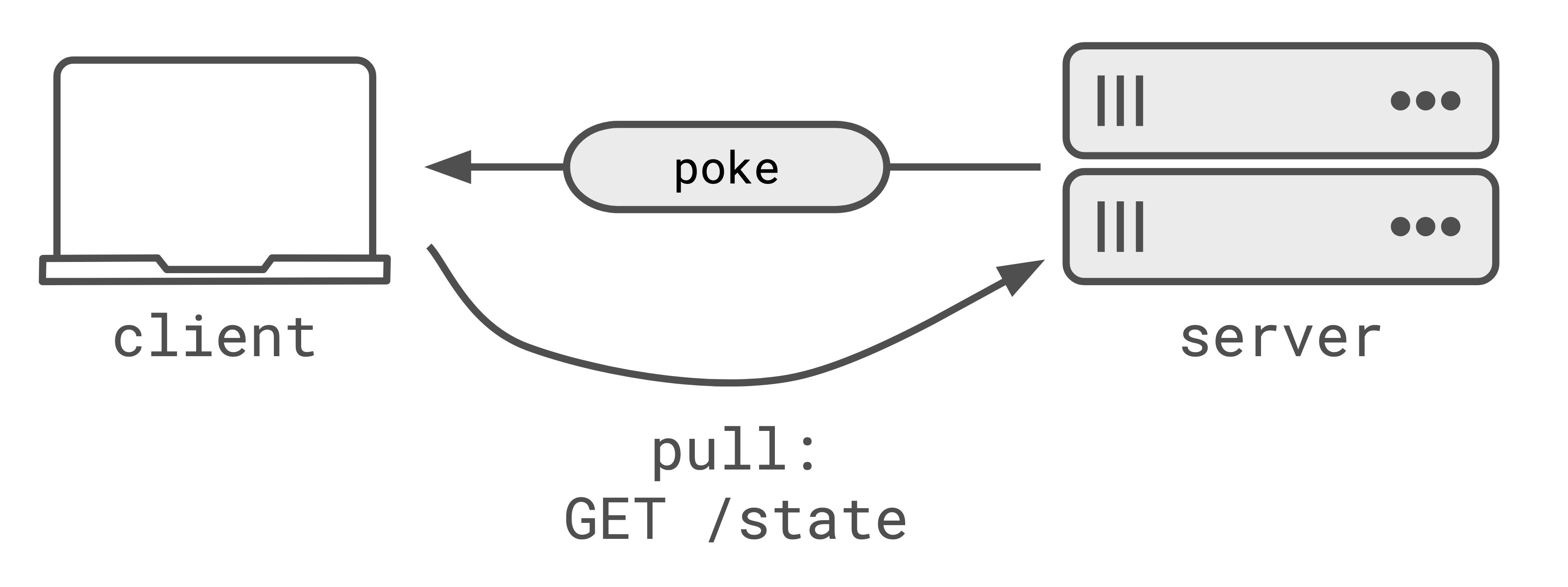

Poke/pull is the easiest pattern to integrate into an existing app. When an update happens on the server a ‘poke’ is sent to all subscribed clients notifying them to fetch the new state.

When a client receives the notification, it will make a request to the server to ‘pull’ the new state. Poke/pull is easy to integrate into an existing app because you can make use of existing endpoints for fetching state, and use ‘realtime’ pokes to notify clients. There’s little extra work to implement the ‘poke’ if you already have the APIs to server the ‘pull’.

The obvious problem here is fan-out. A single update on the server, fanned-out to multiple clients, will trigger multiple clients to pull the new state from the server at the same time.

Caching is pretty affective because all clients are requesting state at the same time, it’s fairly easy to cache the response and serve the same response to all clients. The cached response should remain fresh enough because the clients are all making the ‘pull’ requests at the same time.

The server can also spread the pokes out over a longer duration, which would cause fewer clients to make the ‘pull’ requests at the same time.

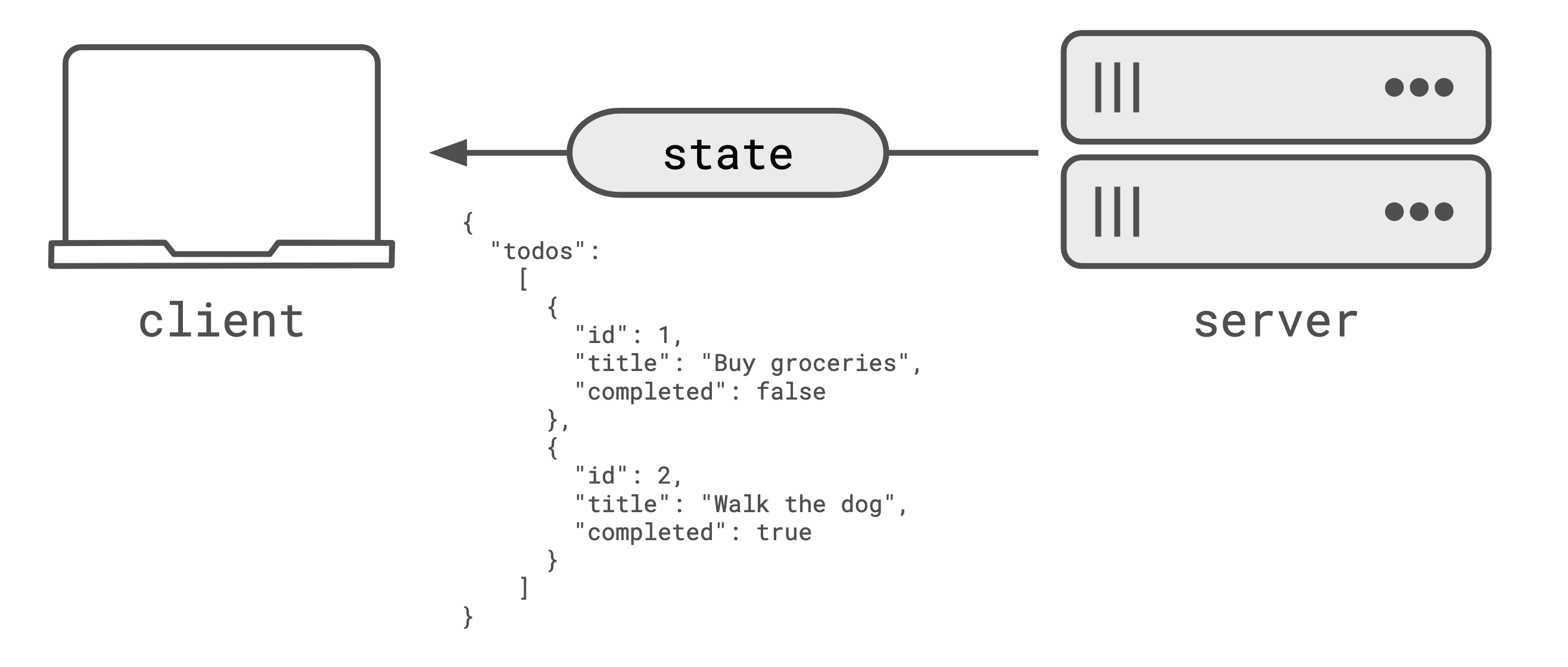

Push state

The second pattern is ‘push state’. In this pattern, the server already knows updated state that the clients should receive so it pushes that state out to the clients. Instead of sending a ‘poke’, as in the poke/pull pattern, the server sends the new state immediately.

This mitigates the fan-out issue as clients receive the updated state immediately, instead of needing to ‘pull’ it. Pushing the state is easy to work with because a clients aren’t likely to become out of sync with the state. On each update the client gets the full copy of the state it should use, so any divergence caused by bugs on the client are quickly mitigated.

Pushing the entire state becomes difficult for the client to make use of if they need to know what

changed. Pushing the entire state also doesn’t scale to large states particularly well, as a small

change in the state will trigger all the state to be re-sent to the client. For example, if “walk

the dog” becomes completed, then that change in state from false to true would trigger all the

“todos” to be sent.

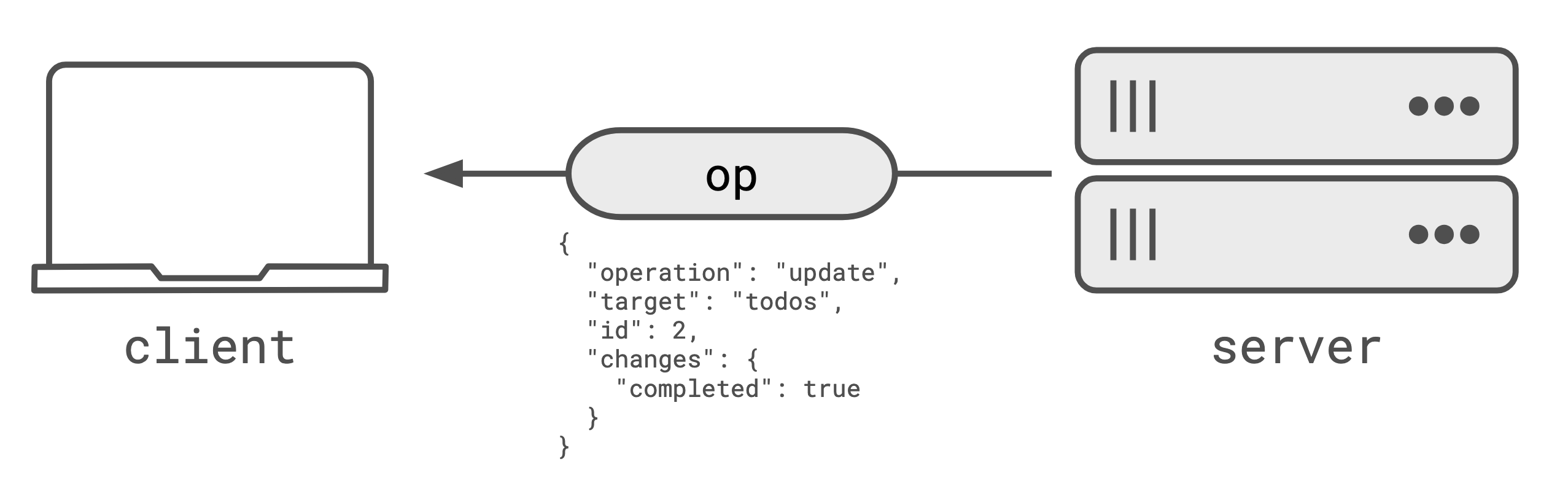

Push ops

Pushing ops (operations) makes it easier for clients to work out what has changed, and reduces the size of the data that needs to be transferred.

It’s fairly likely that the server understands the operation that is causing a change in the state, and sends that operation to connected clients. Instead of sending the entire state, the server sends an operation that can be applied to update the client’s state to match the server’s state.

| |

Like in the example, the operation represents a change in the todo with id: 2,

where the new state is completed: true.

Each clients then merges that operation into their existing state. As mentioned in the ‘Push state’ section, this relies on the server having an accurate understanding of the state on the client. Otherwise the server generated operations aren’t going to bring the client’s state in sync with the server’s.

Finally with push ops, you have to provide an mechanism for the client to get the initial state that the other ops should be applied to. This is often modelled as an “initial” operation to set the state, and the remaining ops are applied on top.

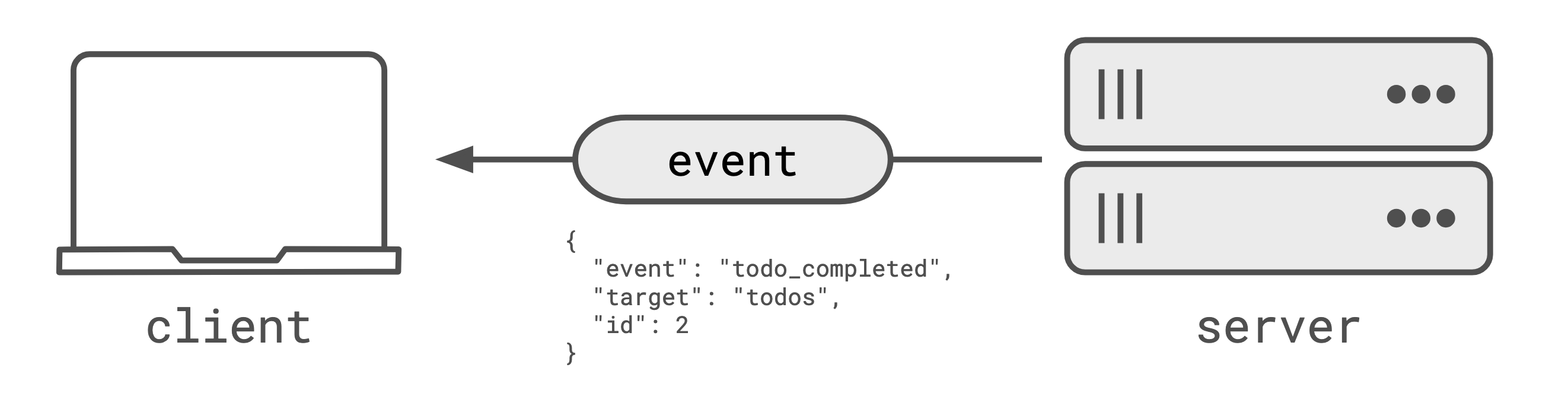

Event sourcing

With event sourcing, the ’event’ that triggered the change is sent to clients rather than; an ‘operation’ that represents the change or the full updated state. For example:

| |

In this example, you can see that the event doesn’t contain the updated state (i.e. completed: true)

and instead contains the “event” that happened. It’s then the client’s responsibility to know what

to do with that event. The purists will argue this is a better data representation, but really it

causes more disparate clients to need to implement the same “business logic” by understanding that

the event means the completed field should be changed to true.

Perhaps, if the client needs to implement more complicated logic than just showing the updated state

then sending the event could be useful, as the client doesn’t have to reverse-engineer that a change

in the field completed to true means that the todo was completed.

Transports

There are a bunch of different transports that you can use to keep the server and client connected; websockets, sse, event-streams, comet, polling (long or short). Each has their pros-and-cons, but they broadly provide the same functionality.

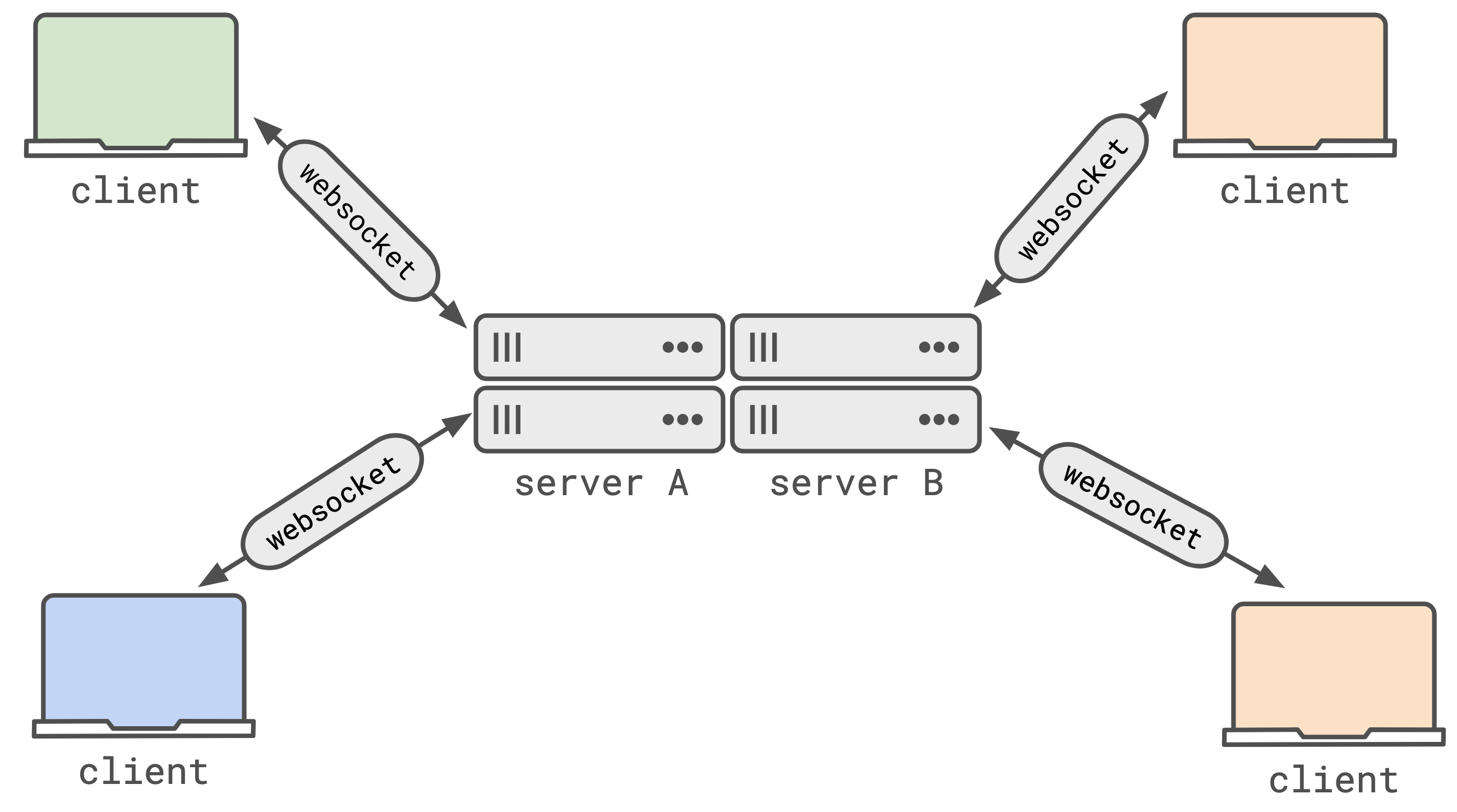

All the transports I listed work over HTTP. This means they all operate pair-wise; server to client. One client is connected to exactly one server. When you have a system that’s horizontally scaled (with multiple replicas of the server), you quickly find that the server that handled the original request which triggered a change in the state won’t be the server that holds all the client connections that you want to push the new state to.

In the image above, the system has two replicas of the server (server A and server B). If the green client makes a change, and shares that with server A via the websocket connection this is pretty easy for server A to share that update with the blue client. But it’s pretty hard for server A to share that update with the two orange clients (connected to server B).

This is really annoying. Typically the point of coordination between horizontally scaled servers is the database, but you don’t really want each replica to be polling the database for changes, or to have to rely on LISTEN/NOTIFY semantics to get notified of the changes.

This is where Pub/Sub providers become pretty useful, as they handle the websocket infra and fan-out for you.